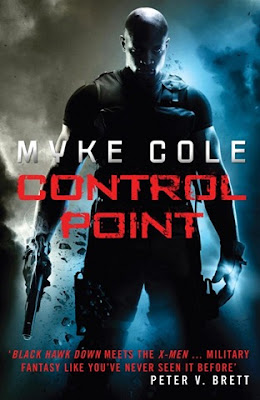

I recently invited SFF authors to write guest blogs for the Hotlist, and a few of them have agreed to do so. The first to step up to the plate was Myke Cole, author of what is still the speculative fiction debut of the year (in this house at least), Shadow Ops: Control Point (Canada, USA, Europe).

For more information about the author and his novels, check out his official website.

Cole wrote an interesting piece on leadership. . .

Enjoy!

------------------------

When you work in and around government, the military and corporate America, people talk a lot about leadership. Actually, that’s an understatement. In major bureaucracies, “leadership” is practically fetishized. You can’t swing a sock without hitting a program manager saying that the attribute they most look for in new hires is “leadership.”

For years that term bothered me. It felt nebulous, protean. One man’s leader is another man’s demagogue. What does it mean to really be a leader? What were the specific attributes that one looked for when grooming the leaders of tomorrow? Nobody could ever tell me.

But now, after a year and a half of full time writing, I think I’m starting to get a window on what it might actually mean.

Here’s one thing I never expected to happen when I got a book deal with a major New York publishing house: arguing a plot/character point with an editor with over 20 years experience picking winning horses and creating literary successes, and having her shrug, smile and say, “Okay, it’s your book.”

And not because she agreed with me, but because ultimately, it’s my name going on the cover. I am the creative nucleus of the project. I am in charge.

I win. I rule. I call the shots.

And that’s fucking terrifying.

Because it also means that if dialogue rings hollow, if the plot holes are big enough to admit a Komatsu Superdozer, then that’s also on me. Nobody is going to write a one star amazon review complaining about how badly editorial fucked this up, or how the art department blew it on the cover, or how marketing failed to get behind the project.

They will blame the author.

That’s me, in case you were wondering.

Beta-readers and friends can give me input. My agent and my editor can help me solve thorny problems, make suggestions on how to make a character’s arc more satisfying, or advise me to abandon an ill-advised plot path and start fresh with something more interesting. But these are suggestions. In the end, I make the call, and I own the consequences and all the friends or institutional connections in the world can’t change that.

That’s the most terrifying thing about being a writer.

And it is also the most terrifying thing about being an officer. I think a lot of writers who sign contracts with big publishing houses expect a huge apparatus to kick in. The machine is oiled by years of experience bringing authors to the marketplace and making sure they sell. After all, if the books don’t sell, the publisher doesn’t make money, so they’ve got a vested interest in your success, right?

The same holds true for newly minted officers. The military is centuries old. It’s a well-oiled machine designed to take in fresh-eyed academy graduates and make sure they know where they’re headed and how to get there. The wolf is the pack and the pack is the wolf. There’s nothing to be gained by letting the new guy fall on his face.

But that’s exactly what happens all the time.

Because officers are leaders. They are ultimately responsible for the units they command. They take credit for the success of their subordinates, but they also answer for their failures. When the big questions are asked, all eyes snap back to you. You are the one who has to make the call, and you are the one who has to answer for the results. Your senior non-commissioned officers will counsel you, make suggestions, give you the benefit of their many years of experience. But in the end? Just like that editor, they will shrug their shoulders and say, “It’s your ship, sir.”

And that’s the irony of this experience of writing full time. Because now I finally understand what leadership is, both in the military and in the arts: It is, first and foremost, ownership. It’s a total personal stake in work. It’s genuinely believing that a project belongs to you in every aspect, and that nobody has more responsibility than you to make it as perfect as possible. It’s the bone-deep sense that even though you are part of a team, you are still personally on the hook for ensuring that every aspect of the work (even aspects over which you have little control) is done to standard: standards that you set, because you are that vested in the success of the work.

The best writers I know fret over covers they haven’t designed. They are willing to go to the mat with a proofreader over the placement of a comma. They will spend days emailing back and forth with their editor over a character’s hair-color. Because it’s their baby, and by God it WILL BE PERFECT.

The best officers are the same way. They track paperwork from end-to-end even when they would be well within their rights to send it off and forget it. They spend hours reading policy manuals that only relate tangentially to their work, because, hey, tangentially related IS STILL RELATED. They know the personal quirks, phobias and goals of every one of their crew, not because they’re nosy, but because they want to help them to do their best work. It’s THEIR SHIP and by God it WILL BE PERFECT.

The relationship between a leader and their project/task, done right, seems closest to the relationship between a parent and a child. At some point, you have to parade your unit or send your artwork out to an audience to be judged. But until the moment that happens? You cannot rest, because good enough is never good enough.

Being a professional writer is nothing like I’d thought it would be. Being a military officer is nothing like I’d thought it would be. Both are eerily similar in defying my expectations.

If you want to do either, and do it right, you’d better be ready to own it down to the thread count.

No comments:

Post a Comment